Dr. Paul D. Parkman, whose research was instrumental in identifying the virus that causes rubella and developing a vaccine that prevented an epidemic of the disease in the United States for more than 50 years, died May 7 at his home in Auburn, New York, in the Finger Lakes region. He was 91 years old.

The cause was lymphoblastic leukemia, said granddaughter Theresa M. Leonardi.

Rubella, also known as German measles because German scientists classified it in the 19th century, is a moderate disease for most patients, identified by a patchy and often itchy red rash. But during pregnancy it can cause the birth of babies with severe physical and mental disabilities and can also cause miscarriages and stillbirths.

In the 1950s, when Dr. Parkman was a pediatric medicine resident at the State University Health Science Center (now SUNY Upstate Medical University) in Syracuse, he once recalled being distressed at showing a new mother her stillborn baby , whose skin rash he would discover. subsequently, probably resulting from the mother's infection with rubella during pregnancy.

In 1964 and 1965, rubella – an epidemic that struck every six to nine years – caused approximately 11,000 pregnancies to be miscarried, 2,100 newborns to die, and 20,000 babies to be born with birth defects.

It was the worst epidemic in three decades and the last rubella epidemic in the United States. The disease was declared eradicated in the Americas in 2015, although the virus has not yet been eradicated in Africa or Southeast Asia.

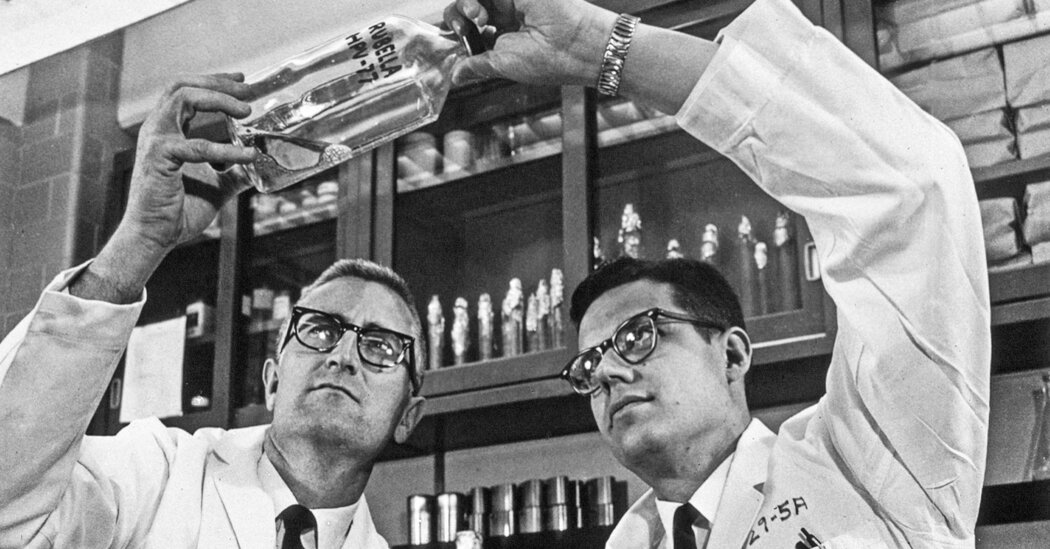

The rubella virus was identified and isolated in the early 1960s by Dr. Parkman and his colleagues at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Maryland, and by a team of researchers at Harvard University led by Thomas H. Weller.

In 1966, Dr. Parkman, Dr. Harry M. Meyer Jr., and their collaborators at the National Institutes of Health, including Maurice R. Hilleman, revealed that they had perfected a vaccine to prevent rubella. Dr. Parkman and Dr. Meyer signed over their patents to the NIH so that vaccines could be produced, distributed, and administered promptly.

“I never made any money from those patents because we wanted them to be freely available to everyone,” he said in an oral history interview for the NIH in 2005.

President Lyndon B. Johnson thanked the researchers, noting that they were among the few who could “count themselves among those who directly and measurably advance human well-being, save precious lives, and bring new hope to the world.”

However, after Dr. Parkman retired from government in 1990, as director of the Food and Drug Administration's Center for Biological Evaluation and Research, he expressed concern about what he called the unfounded skepticism that persisted about the value of vaccines.

“With the exception of drinking water, vaccines have been the most successful medical interventions of the 20th century,” he wrote in 2002 in Food and Drug Administration Consumer, an agency journal.

“When I look back on my career, I've come to think that maybe I got caught up in the easy part,” he added. “It will be up to others to take on the difficult task of maintaining the protections that we fought to obtain. We must prevent the spread of this vaccine nihilism, because if it prevails, our successes could be lost.”

Paul Douglas Parkman was born May 29, 1932, in Auburn and grew up in Weedsport, a nearby village of about 1,200 people. His father, Stuart, was a postal clerk who served on the village board of education and raised poultry to support his son's education. His mother, Mary (Klumpp) Parkman, ran the household.

In 1955, Paolo married a former kindergarten classmate, Elmerina Leonardi. She is his only immediate survivor. His brother, Stuart, and his sister, Phyllis Parkman Thompson, predeceased them.

Enrolled in an accelerated degree program, he received his degree in pre-medicine from St. Lawrence University in Canton. NY, and his medical degree from the State University Health Science Center, both in 1957.

In 1960 he enlisted in the Army Medical Corps as a captain. After serving at Walter Reed as a research scientist, he was chief of the NIH's general virology department from 1963 until the department was absorbed by the Food and Drug Administration in 1972. There, as director of the biological center, he oversaw policy on HIV/AIDS. he testing and approval of a vaccine for the most common cause of bacterial meningitis and have imposed greater scrutiny on blood banks. He retired in 1990 as director of the Center for Biological Evaluation and Research.

Dr. Parkman trained as a pediatrician. That he came to specialize in viruses was both fortuitous and unfortunate.

While stationed at Fort Dix in New Jersey, he was assigned to study the seasonal surge in cold and flu cases among new recruits.

“A runny nose is not a thing to behold,” Dr. Parkman said in the oral history interview. He became passionate about virology, but returned to Washington hoping for a more challenging topic than the common cold. He found it.