This article is part of NeglectedA series of necrologists on extraordinary people whose deaths, starting from 1851, have not been reported on time.

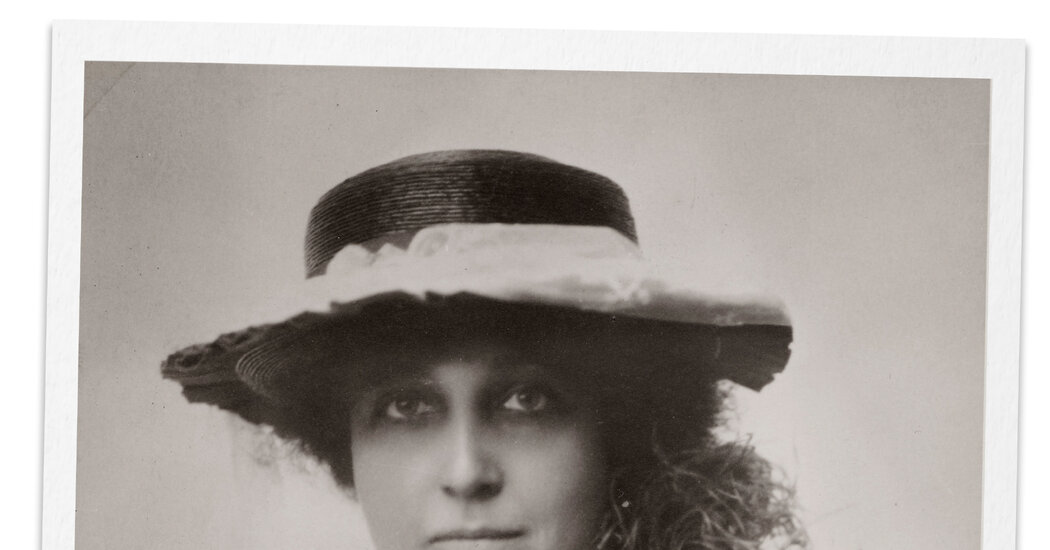

Katharine Dexter McCormick, born from a life of wealth, who aggravated the marriage, could have sat back and simply enjoy the numerous advantages that flow. Instead, he put his considerable luck – combined with his remarkable will – in making life better for women.

Activist, philanthropist and benefactor, McCormick used his wealth strategically, in particular to sign the basic research that led to the development of the birth control pill in the late 1950s.

Before then, the contraception in the United States was extremely limited, with prohibitions on diaphragms and condoms. The advent of the pill made it easier for women to plan when and if to have children, and fueled the explosive sexual revolution of the 60s. Today, the pill, despite some side effects, is the most used form of reversible contraception in the United States.

McCormick’s interest in birth control began in the 10s, when he learned of Margaret Sanger, the feminist leader who had been imprisoned for the opening of the first nation’s birth control clinic. He shared Sanger’s fervent belief that women should be able to trace their biological destinies.

The two met in 1917 and soon a scheme developed to smug the diaphragms in the United States were developed.

The diaphragms had been prohibited pursuant to the Comstock Act of 1873, which made a federal crime to be sent or deliver through the “obscene or lewd” mail. (The law, which still prohibits shipments relating to abortions, received renewed attention since the federal law to abortion was canceled in 2022.)

McCormick, who was fluent in French and German, traveled to Europe, where the diaphragms were commonly used. He had studied biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was able to lay as a scientist in meetings with diaphragms producers.

“He purchased hundreds of devices and took local seamstress to sew them in clothes, evening dresses and coats”, according to a 2011 article in Mit Technology Review. “Then he had the garments wrapped and packaged neatly in trunks for shipping.”

She and her steamer trunks have passed the customs. If the authorities had stopped it, the article said, they would not have found “nothing but slightly swollen clothes in possession of a domineering socialite, a woman who exuded this importance of self and overturning her porters so great that nobody suspected something”.

From 1922 to 1925, McCormick clandestinely introduced more than 1,000 diaphragms in Sanger’s clinics.

After the death of her husband in 1947, McCormick inherited a considerable amount of money and asked for advice to Sanger on how to put him to use advanced contraception research. In 1953, Sanger introduced her to Gregory Goodwin Pincus and Min-Chueh Chang, researchers from the Writster Foundation for Experimental Biology in Massachusetts, who were trying to develop a safe and reliable oral contraceptive.

He was enthusiastic about their work and provided almost all funding – $ 2 million (about $ 23 million today) – necessary to develop the pill. He even moved to WoCester to monitor and encourage their research. Pincus’s wife, Elizabeth, described McCormick like a warrior: “Little old man was not. He was a granadier.”

Katharine Moore Dexter was born in a rich socially activist family on August 27, 1875 in Dexter, Michigan, west of Detroit. The city was named for its grandfather, Samuel W. Dexter, who founded him in 1824 and maintained an underground stop in his home, where Katharine was born; His great -grandfather, Samuel Dexter, was secretary to the treasure under President John Adams.

Katharine and her older brother, Samuel T. Dexter, grew up in Chicago. Their mother, Josephine (Moore) Dexter, was a Boston Brahmin who supported women’s rights. Their father, Wirt Dexter, was a great power lawyer who was president of the Chicago Bar Association and as director of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. He also led the rescue committee after the great Chicago fire in 1871 and was an important real estate developer.

Katharine’s father died when he was 14 years old. A few years later, his brother died of meningitis as he attended the Harvard Law School. Those first deaths indicated a career in medicine.

He attended MIT and graduated in Biology, rare successes for a woman of that era. It came with a mind of her own and successfully challenged a rule that the students had to wear hats at all times, claiming that they represented a danger of fire in the scientific workshops. She graduated in 1904 and planned to attend the medical school.

But at that point, he had started to go out with the crazy Stanley Robert McCormick, who had known in Chicago and who was the heir of an immense fortune built on a mechanical collection machine that his father had invented. As a young lawyer, he contributed to negotiating a merger who made his family an important owner of International Harvester; In 1909, it was the fourth largest industrial company in America, measured in activity.

McCormick convinced Katharine to marry him instead of going to medical school. They married his mother’s castle in Switzerland and settled in Brookline, Mass.

But even before getting married, he had shown signs of mental instability and started experimenting with violent and paranoid disappointments. He was hospitalized with what was later determined to be schizophrenia and remained under psychiatric care – mainly at Riven Rock, the McCormick Family Estate in Montecito, in California – until his death. He has never divorced him and never remarried. They had no children.

Katharine McCormick spent careless decades in personal, medical and legal disputes with his husband’s brothers. They fought for its treatment, its protection and finally its property, as detailed in an article in 2007 in Prologue, a publication of the national archives. He was his only beneficiary, inheriting about $ 40 million ($ 563 million in today’s dollars). In combination with $ 10 million (over $ 222 million today) he had inherited from his mother, who made him one of the richest women in America.

While her husband’s disease consumed her personal life, McCormick threw himself in social causes. He contributed financially to the suffrage movement, he held speeches and roses in leadership to become treasurer and vice -president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. After the women won the right to vote in 1920, the association evolved in the League of Women voters; McCormick became his vice president.

In 1927, he founded the Neuroendocrine Research Foundation at the Harvard Medical School, believing that a malfunctioning adrenal gland was responsible for his husband’s schizophrenia. He provided financing for two decades and acquired an experience in endocrinology which he later informed his interest in the development of an oral contraceptive.

After the FDA approved the pill, McCormick turned his attention to the financing of the first residence on the campus for women at MIT when he studied there, women had no housing, one of the numerous factors that discouraged them from applying. “I believe that if we can make them accommodate adequately,” he said, “that the best scientific instruction in our country will be open to them permanently”.

McCormick Hall, called for her husband, opened on the Institute’s Cambridge campus in 1963. At the time, women made up about 3 percent of school university students; Today they represent about 50 percent.

When he died of a stroke on December 28, 1967, in his home in Boston, McCormick had played an important role in the expansion of opportunities for women in the 20th century. He was 92 years old.

In addition to a short article in Boston Globe, his death has made little notice. The subsequent necrologists of birth control researchers who had supported did not mention his role in their success.

In his will, he left $ 5 million (over $ 46 million today) to the Planned Parenthood Federation and $ 1 million (over $ 9 million today) at Pincus laboratories. Previously, he had donated his property inherited in Switzerland to the United States government to be used by his diplomatic mission in Geneva. Has left most of the rest of his property to MIT