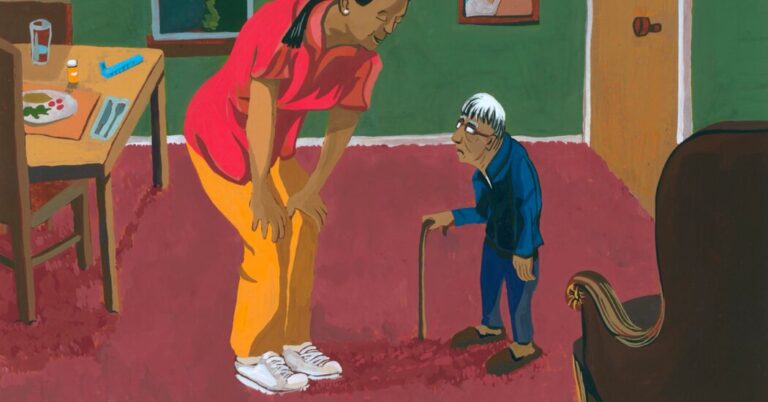

A first example of Elderspeak: Cindy Smith was visiting with her father in her living apartment assisted in Roseville, California. A helper who was trying to induce him to do something – Mrs. Smith no longer remembers what – he said: “Let me help you, honey”.

“He just looked at her – under his thick eyebrows – and said:” What do we get married? “” Smith, who made a nice laugh, said, said.

His father was then 92, a retired county planner and a veteran of the Second World War; Macuular degeneration had reduced the quality of his vision and used a walking for movement, but remained cognitively acute.

“Normally it wouldn't have become too icy with people,” said Mrs. Smith. “But he had the feeling that he had grown up and was not always treated as one.”

People almost understand what “Elderspeak” means. “It is a communication for older adults who sounds like Talk Baby,” said Clarissa Shaw, dementia care researcher at the University of Iowa College of Nursing and co -author of a recent article that helps researchers to compensate for its use.

“It derives from an assumption of fragility, incompetence and dependence.”

Its elements include inappropriate enthusiasm. “Elderspeak can be checked, a little overbearing, so soften that message is” Honey “,” Dearia “,” sweetness “, said Kristine Williams, a gerontologist nurse of the University of Kansas School of Nursing and another COMPART.

“We have negative stereotypes of the elderly, so let's change the way we talk.”

Or caregiver can resort to plural pronouns: Are we ready to swim? There, the implication “is that the person is unable to act as an individual,” said dr. Williams. “I hope he doesn't take the bath with you.”

Sometimes, the elderly use a stronger volume, shorter phrases or simple words slowly intoned. Or they can adopt an exaggerated vocal quality and singer more suitable for preschool children, together with words such as “Vasino” or “Jammies”.

With the so-called tags questions It's time to have lunch now, right? – “You are asking them a question but you are not allowing them to answer,” explained Dr. Williams. “You're telling them how to answer.”

Studies in the nursing homes show how trivial this speech is. When Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw and their team analyzed the video recordings of 80 interactions between staff and residents with dementia, discovered that 84 % had involved some form of Elderspeak.

“Most of Elderspeak is well understood. People are trying to show that they worry,” said dr. Williams. “They don't realize the negative messages that arrive.”

For example, among the residents of the nursing homes with dementia, the studies have found a relationship between exposure to Elderspeak and behaviors collectively known as treatment resistance.

“People can go away or cry or say no,” explained Dr. Williams. “They could tighten their mouth when you are trying to feed them.” Sometimes, they push away the caregiver or hit them.

She and her team developed a training program called chat (to change the speeches), three hours sessions that include communication videos between staff and patients, intended to reduce Elderspeak.

It worked. Before training, in 13 cure houses in Kansas and Missouri, almost 35 % of the time spent in the interactions consisted of Elderspeak; That number was only about 20 percent later.

At the same time, resistant behaviors represented almost 36 percent of the times spent in the meetings; After training, this proportion dropped to about 20 percent.

A study conducted in a Midwest hospital, always among patients with dementia, found the same type of decline as the resistance behavior.

In addition, chat training in the nursing homes was associated with the lower use of antipsychotic drugs. Although the results have not achieved a statistical meaning, in part due to the small size of the sample, the research team considered them “clinically significant”.

“Many of these drugs have a black box that warns from the FDA,” said dr. Williams of drugs. “It is risky to use them in fragile and elderly” because of their side effects.

Now, Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw and their colleagues have simplified the formation of the chat and have adapted it for online use. They are examining its effects in about 200 nationwide cure homes.

Even without formal training programs, individuals and institutions can fight Elderspeak. Kathleen Carmody, owner of Senior Matters Home Care and advice in Columbus, Ohio, warns his helpers to contact customers such as Mr. or Mrs. or Ms.

In long -term care, however, families and residents can worry that correcting the way they speak staff members could create antagonisms.

A few years ago, Carol Fahy was smoking the way the assistants in a living structure assisted on the outskirts of Cleveland treated his mother, who was blind and had become increasingly employee in his 80s.

By calling her “sweetness” and “small honey”, the staff “got up and got up their hair in two braids on top of the head, as you would do with a child,” said Mrs. Fahy, 72 years old, psychologist in Kaneohe, Hawaii.

Although he recognized the pleasant intentions of the assistants, “there is a falsehood in this regard,” he said. “He doesn't make someone feel good. In reality he is alienated.”

Mrs. Fahy considered she discussing her objections with the assistants, but “I didn't want them to sell themselves”. In the end, for several reasons, he moved his mother to another structure.

Yet objecting to Elderspeak must not become contradictory, said dr. Shaw. Residents and patients – and the people who meet Elderspeak elsewhere, because they do not limit themselves to limiting the health settings – they can politely explain how they prefer to be pronounced and how they want to be called.

Cultural differences also come into play. Felipe Agudelo, who teaches health communications at the University of Boston, underlined that in some contexts, a limit or a term of affection “does not derive from underestimating your intellectual ability. It is a term of affection.”

He emigrated from Colombia, where his 80 -year -old mother did not offend when a doctor or health worker asks her for “Tómese la Mealita” (take this small pill) or “Mueva La Manito” (move your hand).

It is customary and “he feels he is talking to someone he cares about,” said dr. Agudelo.

“Come to a place of negotiation,” he recommended. “It doesn't have to be a challenge. The patient has the right to say:” I don't like it that you talk to me that way. “”

In return, the worker “should recognize that the recipient may not come from the same cultural background,” he said. That person can answer: “This is the way I usually speak, but I can change it”.

Lisa Greim, 65 years old, retired writer in Arvada, in Collo.

Suddenly, he told in an e-mail, a correspondence pharmacy started calling almost every day because he had not filled a prescription as expected.

These “delicately condescending” calls, apparently reading from a script, everyone said: “It is difficult to remember to take our medicines, right?” – As if they were all swallowing the pills together with Mrs. Greim.

Annoyed by their presumption and their follow-up demand on what has frequently forgotten her drugs, Mrs. Greim informed them that after having made previously, she had a sufficient supply, thanks. He would have reordered when he needed more.

So, “I asked them to stop calling,” he said. “And they did it.”

The new old age is produced through a partnership with Kff's health news.