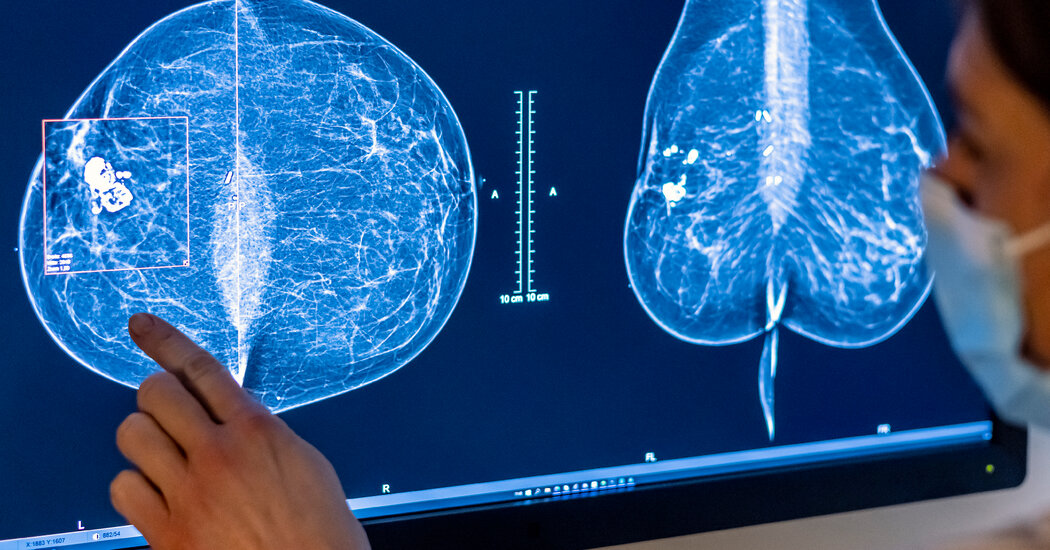

Citing rising rates of breast cancer in young women, an expert panel on Tuesday recommended starting regular mammography screening at age 40, reversing long-standing and controversial guidance that most women wait up to 50 years old.

The committee, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, finalized a draft recommendation made public last year. The group issues influential advice on preventative health, and its recommendations are generally widely adopted in the United States.

In 2009, the task force raised the age to begin routine mammograms from 40 to 50, sparking widespread controversy. At the time, researchers feared that early screening would cause more harm than good, leading to unnecessary treatments in younger women, including alarming findings that led to invasive but ultimately futile procedures.

But breast cancer rates among women in their 40s are now on the rise, rising 2% a year between 2015 and 2019, said Dr. John Wong, vice chair of the task force. The panel continues to recommend screening every two years for women at average risk for breast cancer, although many patients and providers prefer annual screening.

“There is strong evidence that starting screening every two years at age 40 offers sufficient benefit to recommend it to all women in this country to help them live longer and have a better quality of life,” the Dr Wong, GP. physician at Tufts Medical Center who is the director of comparative effectiveness research for the Tufts Clinical Translational Science Institute.

The recommendations have come under harsh criticism from some women's health advocates, including Rep. Rosa DeLauro, Democrat of Connecticut, and Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Democrat of Florida, who say the advice doesn't go far enough.

In a letter to the task force in June, they said the guidance continues to “fall short of the science, create gaps in coverage, generate uncertainty for women and their providers, and exacerbate health disparities.”

Again weighing in on a hotly debated topic, the task force also said there is insufficient evidence to approve additional scans, such as ultrasound or MRI, for women with dense breast tissue.

This means that insurers do not have to provide full coverage of additional screening for these women, whose cancers can be missed by mammography alone and who are at increased risk of breast cancer. About half of women aged 40 and older fall into this category.

In recent years, the law has required more mammography providers to tell women when they have dense breast tissue and to tell them that mammography may be a poor screening tool for them.

Starting in September, all mammography centers in the United States will be required to provide patients with this information.

Doctors often order additional or “supplemental” scans for these patients. But these patients often find themselves having to pay all or some of the costs themselves, even when additional tests are performed as part of preventive care, which by law should be offered free of charge.

Medicare, the government health plan for older Americans, does not cover the additional scans. In the private insurance market, coverage is fragmented, depending on state laws, the type of plan and its design, among other factors.

The task force sets standards for which preventive care services must be covered by law by health insurers at no cost to patients.

The panel's decision not to approve the additional scans has significant implications for patients, said Robert Traynham, a spokesman for AHIP, the association representing health insurance companies.

“What this means for coverage is that there is no mandate to cover these specific screenings for women with dense breasts with zero-dollar cost sharing,” she said.

While some employers may choose to do so, this is not required by law, Traynham said.

Kathleen Costello, a retiree from Southern California who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2017 when she was 59, said she is convinced that mammograms did not detect cancer for many years.

She underwent screening every year, and every year she received a letter saying she was cancer-free. Her letters also told her that she had dense breast tissue and that additional screening was available but not covered by insurance.

Six months after a full-body mammogram in 2016, she told her doctor that her right breast was firm. The doctor ordered a mammogram and an ultrasound.

“Within 30 seconds, the ultrasound detected the cancer,” Ms. Costello said in an interview, adding that she knew because “the technician turned pale and left the room.”

The mass was four centimeters in size, Costello added: “It's difficult for me to accept that it has grown in six months from undetectable to four centimetres.”

But Dr Wong, of the task force, said there is no scientific evidence to show that additional imaging, using MRI or ultrasound, reduces the progression of breast cancer and extends the lives of women with dense breast tissue.

There is ample evidence, on the other hand, that additional screening can lead to frequent false-positive results and biopsies, contributing to stress and unnecessary invasive procedures.

“It's tragic,” Dr. Wong said. “We are as frustrated as the women are. They deserve to know if additional screening would be helpful.”

But medical organizations like the American College of Radiology advocate additional screening for women with dense breast tissue. There is research showing that ultrasound combined with mammography detects additional cancers in patients with dense tissue, said Dr. Stamatia Destounis, chair of the university's breast imaging committee.

For women with dense breasts who are at average risk of breast cancer, recent research indicates that MRI is the best supplemental scan, Dr. Destounis said, “with far better cancer detection and higher positive predictive values.” favorable.”

The college also recommends annual screening for women at average risk for cancer, rather than screening every two years as recommended by the panel. The group of radiologists is pushing for a recommendation that all women should be assessed for breast cancer risk before age 25, so that high-risk women can begin screening even before they turn 40.

Growing evidence shows that Black, Jewish and other minority women develop breast cancer and die from it before age 50 more frequently than other women, Dr. Destounis noted.

Trans men who have not had mastectomies should continue to undergo breast cancer screening, she added, and trans women, whose hormone use puts them at greater risk of breast cancer than the average man, should discuss screening with your doctor.

While the panel's advice to start screening at age 40 is “an improvement,” Dr. Destounis said, the final recommendations are “not enough to save women's lives.”