Dr. Joel Breman, an infectious disease specialist who was part of the original team that helped fight the Ebola virus in 1976, died April 6 at his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, at age 87.

His death was confirmed by his son, Matthew, who said his father died of complications from kidney cancer.

“We were scared to death,” Dr. Breman, recalling his pioneering mission, told a National Institutes of Health newsletter in 2014, as a new and even deadlier Ebola epidemic raged that year.

Nearly 40 years earlier, his team of five had just landed in the interior of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, at a remote Roman Catholic mission hospital. They found themselves faced with an unnamed viral infection, the origin of which was unknown, and which was accompanied by high fever and bleeding that led to a quick and painful death.

Dr. Breman, sent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, had only what he described to the NIH as “the most basic protective gear” against the disease, as opposed to the spacesuit-like gear that was standard in the next blast. He and other team members, working in intense heat and bitten by sandflies, “developed rashes and didn't know if we would get the virus too,” he said.

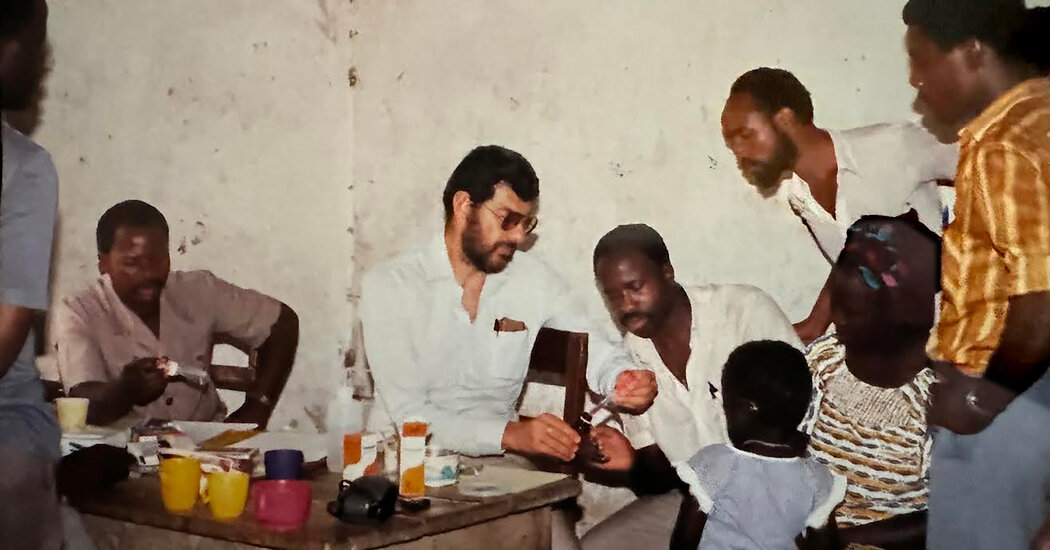

But he calmly began to employ the techniques he had refined on previous missions to Africa, in anti-smallpox initiatives in Guinea and Burkina Faso. He interviewed patients and witnesses, traveling from village to village and going from house to house. He and his colleagues, he recalled, soon determined that the infection had “spread through close contact with infected bodily fluids” and that it had spread in a rural hospital that used unsterilized needles.

Over a long career, spent largely at the Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization and the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Breman worked to eliminate deadly tropical diseases such as smallpox, malaria and the Guinea worm. But that initial Ebola epidemic, he told an interviewer in 2009, “was the scariest epidemic of my entire medical career and perhaps of the last century.”

Compared to the subsequent epidemic in West Africa, which lasted more than two years, the Congo (then Zaire) epidemic was quickly contained. There were fewer than 300 deaths, a stark contrast to the more than 11,000 from 2014 to 2016. The relative success in 1976 was in part due to Dr. Breman's efforts to analyze, contain, and isolate this frightening new virus.

“He was my mentor and he was the leader of the team,” said Dr. Peter Piot, former director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and himself a pioneer in Ebola and AIDS research.

“He already had a lot of experience in epidemic investigations and field work,” Dr Piot continued. “He was a combination of walking encyclopedia and accumulated experience. He had an incredible commitment to solving people's problems, to reaching people and listening to them.”

Dr. Breman spent half an hour or more simply chatting with village notables, about their families and other matters, before moving on to questions about the disease, Dr. Piot said. “He created the link between human understanding and interaction and data analysis. He had the human factor”.

Dr. Piot particularly praised Dr. Breman's behavior: “He remained calm. This was quite a stressful time. Many people died. He was very patient with me.”

Dr. Breman spent two months in the Congo, becoming chief of surveillance, epidemiology and mission control. He was then sent by the CDC to help run the World Health Organization's smallpox program in Geneva.

In 1980, with smallpox effectively eradicated – “one of the greatest triumphs in the history of medicine,” he called it in a Story Corps interview with his son – Dr. Breman began what he called “a new career” running the disease control. antimalarial program.

In a memorial tribute held April 9, Dr. Rick Steketee, a fellow of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, said that in the years since, and through new assignments, Dr. Breman “has written book chapters that guide medicine and public health practice throughout the world and has modified textbooks that have influenced the practice of infectious disease control and elimination, especially in low-resource countries.” Dr. Breman served as president of the company in 2020.

Joel Gordon Breman was born December 1, 1936, in Chicago to Herman Breman, a painting contractor, and Irene (Grant) Breman. When Joel was 7, the family moved to Los Angeles, where his father painted movie sets and his mother bought and sold furniture and property.

Dr. Breman attended Hamilton High School in Los Angeles. He earned a bachelor's degree in political science from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1958 and a medical degree from the University of Southern California in 1965. He earned a bachelor's degree from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 1971.

His first foreign assignment was in Guinea, from 1967 to 1969, when the CDC assigned him to manage the smallpox eradication program. That mission fueled a lifelong passion for Africa, Matthew Breman said. Numerous scientific trips followed, often as a consultant to the World Health Organization.

Dr. Breman held numerous senior positions at the National Institutes of Health, from which he retired in 2010 as senior scientist emeritus.

In addition to his son, he is survived by his wife Vicki; his daughter, Johanna Tzur; and six grandchildren.

“My father loved helping others and thought it was important to help everyone,” Matthew Breman said. “I think that's one of the reasons he went into medicine.”