Philip Sunshine, a Stanford University doctor who played an important role in establishing neonatology as a medical specialty, revolutionizing the care of premature and serious infants who previously had little chance of survival, died on April 5 at his house in Cupertino, California. It was 94.

His death was confirmed by his daughter Diana Sunshine.

Before Dr. Sunshine and a handful of other doctors were interested in taking care of the premiers in the late 1950s and 1960s, more than half of these unimaginably fragile patients died shortly after birth. Insurance companies would not pay to treat them.

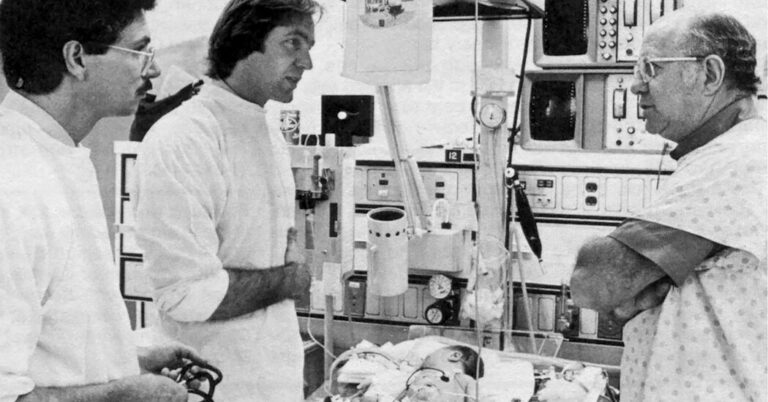

Dr. Sunshine, a pediatric gastroenterologist, thought that many premature children could be saved. In Stanford, he pushed for teams of multiple disciplines to treat them in special intensive care units. Together with his colleagues, he opened the way to the methods of powering the premiers with the formula and helping breathing with the fans.

“We were able to keep children who would not survive, said dr. Sunshine in 2000 in an interview with oral history with the Centro of Pediatric History of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “And now everyone gives this just for granted.”

The early 1960s were a turning point in the care of premature children.

According to Oxford English Dictionary, the word neonatology was used for the first time in the 1960 book “Diseases of the newborn” by Alexander J. Schaffer, a pediatrician in Baltimore. At that point, the Stanford Neonatology Department – one of the first in the country – was active and working.

In 1963, the second son of President John F. Kennedy, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, was born almost six premature weeks. He died 39 hours later. The crisis took place on the front pages of newspapers across the country, pressing on the federal health authorities to start allocating money for neonatal research.

“The story of Kennedy was a great turning point,” said dr. Sunshine in Aha News, a publication of the American Hospital Association, in 1998. “After which, the money of federal research for neonatal assistance have become much easier to obtain”.

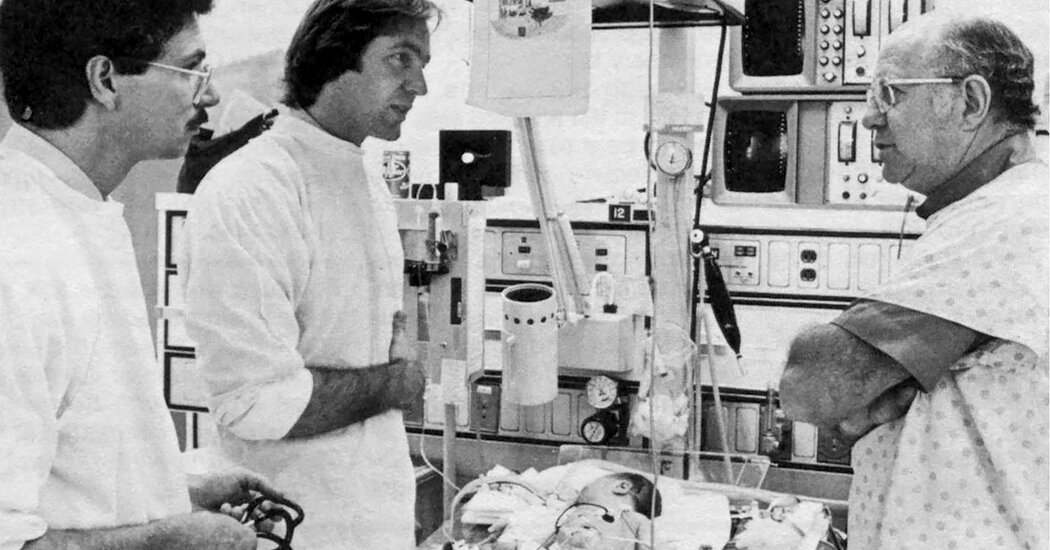

As head of the Stanford Neonatology department from 1967 to 1989, Dr. Sunshine contributed to training hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of doctors who continued to work in neonatal intensive care units all over the world. When he retired in 2022, at the age of 92, the survival rate for children born at 28 weeks was over 90 percent.

“Phil is one of the” original “in neonatology, a neonatologist of a neonatologist, one of the best in our history”, David K. Stevenson, successor of Dr. Sunshine as head of the Stanford neonatal department, wrote in the Journal of Perinology in 2011. “He is comfortably among the great leaders in Neonatology and is simply a department.

Dr. Sunshine has recognized that the care of prehemies required both technical competence and human connection. He urged hospitals to allow parents to visit the neonatal intensive care units so that they could keep their children, perceiving that the contact of the skin skin between mothers and children was beneficial.

He also gave nurses more autonomy and encouraged them to speak when they thought the doctors were wrong.

“Our nurses have always been very important custodians,” said dr. Sunshine in oral history. “Throughout my career, I worked with a nursing staff who often recognized the problems in the child before the doctors did it, and they still do it now. Well, we were learning neonatology together.”

Cecele Quantlance, a neonatal nurse who worked with Dr. Sunshine for more than 50 years, said in a blog post for the health of the children of Stanford Medicine that “there is this profound kindness in Phil – for children, for us, for everyone”.

“Everyone has the same level of importance for him,” he said, adding: “I saw the families cry when it went out of service because they were so attached to him”.

The hours were long; The pressure was extraordinary.

“It was a calming and reassuring presence and totally unstoppable,” said dr. Stevenson in an interview. “He would say:” If you intend to spend the tail all night in the hospital, what better way to do it if not giving someone 80, 90 years of life? “”

Philip Sunshine was born on June 16, 1930 in Denver. His parents, Samuel and Mollie (Fox) Sunshine, owned a pharmacy.

He graduated from the University of Colorado in 1952, and then remained there for the School of Medicine, graduating in 1955.

After his first year of residence in Stanford, he was enrolled in the United States Navy and served as a lieutenant. When he returned to Stanford in 1959, he trained under Louis Gluck, a pediatrician who later developed the modern unit of neonatal intensive care at Yale University.

“He excited me to take care of infants and made everything so interesting,” said dr. Sunshine.

At the time there were no neonedological scholarships, therefore Dr. Sunshine pursued advanced training in pediatric gastroenterology and a scholarship in pediatric metabolism.

“This was a very exciting moment,” he said in the blog post on the health of Stanford Medicine's children. “People with various backgrounds were bringing their skills to the care of newborns: lungs, cardiologists, people like me who were interested in the gastrointestinal problems of babies. I collected a lot of information and enthusiasm from them and we had many opportunities to change the way the children were treated.”

Dr. Sunshine married Sara Elizabeth Vreeland, known as Beth, in 1962.

Together with his wife and daughter Diana, he survived four other children, Rebecca, Samuel, Michael and Stephanie; and nine grandchildren.

In many ways, Dr. Sunshine's surname was an aponian – an ideal word for his occupation and his way of being.

“Totally separated from being the father – or the grandfather – of neonatology, he really brought the sun to every room,” said Susan R. Hintz, a neonatologist in Stanford, in an interview. “It was a relaxing presence, especially in these very stressful moments. The nurse always said to me,” is what everyone remembers. “”