Consciousness can be a mystery, but this does not mean that neuroscientists have no explanation for this. Far from it.

“In the field of consciousness, there are already so many theories that we do not need more theories,” said Oscar Ferrante, neuroscientist of the University of Birmingham.

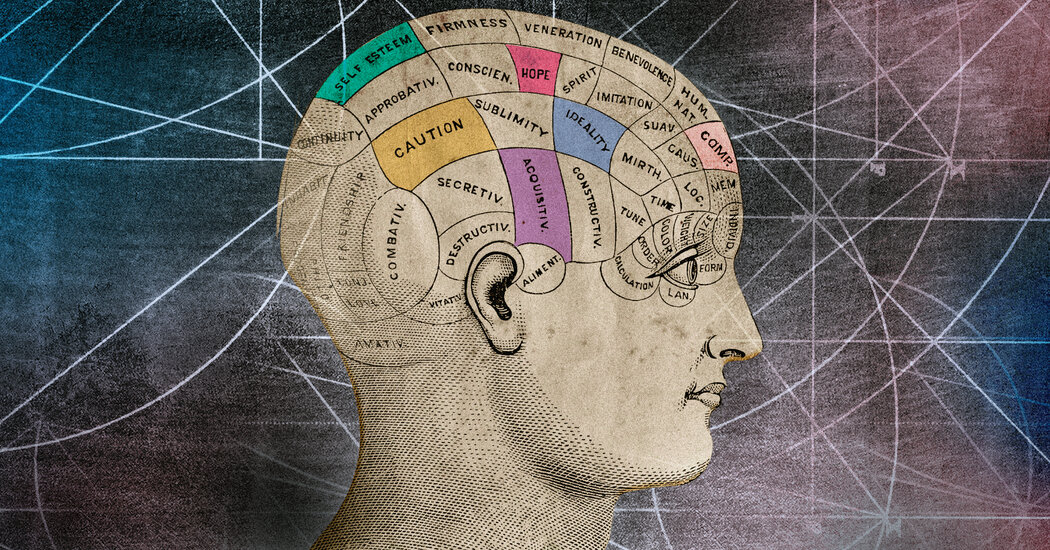

If you are looking for a theory to explain how our brains give rise to subjective and inner experiences, you can verify the theory of adaptive resonance. Or consider the theory of the dynamic nucleus. Do not forget the representative theory of the first order, not to mention the theory of competition of the semantic pointer. The list continues: a 2021 survey identified 29 different theories of consciousness.

Dr. Ferrante belongs to a group of scientists who want to lower that number, perhaps even to one. But they face a steep challenge, thanks to how scientists often study consciousness: they devise a theory, they manage experiments to build evidence for it and claim that it is better than the others.

“We are not incentivized to kill our ideas,” said Lucia Melloni, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Empiric Extetics in Frankfurt, in Germany.

Seven years ago, Dr. Melloni and another 41 scientists have undertaken an important study on the consciousness that hoped would have broken this scheme. Their plan was to bring together two rival groups to design an experiment to see how well both theories foresee what happens in our brain during a conscious experience.

The team, called Cogita Consortium, published its results on Wednesday in the Nature magazine. But along the way, the study became subject to the same elbow conflicts that they had hoped to avoid.

Dr. Melloni and a group of similar scientists began to develop plans for their study in 2018. They wanted to try an approach known as a contradictory collaboration, in which scientists with opposing theories combine forces with neutral researchers. The team has chosen two theories to test.

One, called global neuronal work area theory, was developed in the early 2000s by Stanislas Dehane, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France in Paris and his colleagues. Their theory claims that we consciously experience the world when the key regions in the front of the brain transmit sensory information throughout the brain.

The other theory, developed by Giulio Tononi of the University of Wisconsin and his colleagues, presents himself with the name of integrated information theory. Instead of assigning consciousness to particular parts of the brain that do particular things, this theory begins with the basic characteristics of conscious experiences: they feel specific for ourselves, for example, and are rich in details that form a coherent, complex and unified set – such as the experience of Memories of Marcel Proust who flooded while making the mood of a Madelein.

The researchers therefore asked what kind of physical network – a brain or other – could produce that experience. They concluded that it must involve the processing of a lot of information in numerous different compartments, which therefore transmit information to other compartments, creating an integrated experience.

The Cogita Consortium has mapped an experiment that could test both theories. The champions of the two theories approved him.

“It was particularly beautiful, because it was the first time that these people were trying to solve their disagreements instead of making this parallel game,” said Dr. Melloni.

But she and her colleagues knew that the contradictory collaboration would be a huge company. They recruited a number of young researchers, including Dr. Ferrante, and then spent two years to design the experiment and put their laboratory equipment through trial races. Starting from the end of 2020, they began to scan the brain of 267 volunteers, working in eight workshops in the United States, Europe and China.

The researchers made volunteers play video games to measure their conscious awareness of seeing things. In one of these games, the participants captured colorful records while tightening. Sometimes even a blurred face moved to the screen and the volunteers pressed a button to indicate that they noticed it.

For the utmost understanding, the researchers used three different tools to measure the brain activity of the volunteers.

Some volunteers, who have undergone surgery for epilepsy, agreed to temporarily insert the electrodes in the brain. A second group had scanned the brain from the FMRI machines, which measured the blood flow in the brain. The researchers studied a third group with magnetoencephalography, which records the magnetic fields of a brain.

By 2022, the researchers had moved on to analyze their data. All three techniques provided the same overall results. Both theories made some accurate forecasts on what was happening in the brain while the subjects consciously experienced images. But they also made predictions that have proven wrong.

“Both theories are incomplete,” said dr. Ferrante.

In June 2023, Dr. Melloni revealed the results in a conference in New York. And Cogitati Consortium published the online results and sent them to Nature, hoping that the magazine will publish his document.

Hakwan Lau, a neuroscientist of Sungkyunkwan University to whom he was asked to serve as the auditor, issued a negative judgment. He felt that the Cogita Consortium had not carefully arranged exactly where in the brain he would test the forecast of every theory.

“It is difficult to make a convincing case that the project really puts the theories in a significant way,” wrote dr. Lau in his review in July.

Dr. Lau, who opened the way to his own theory of consciousness, published his online evaluation that August. So he contributed to writing an open letter that criticizes both the cogged experiment and the integrated information theory. A total of 124 experts signed it.

The group, which was called “concerning iit”, directed most of its criticisms to integrated information theory. They called him pseudoscience, quoting widespread attacks that scientists have made on theory in recent years.

These critics have noticed that the theory of integrated information is much more than a simple theory on how our brains work: if any system capable of integrating information is aware, then plants could also be conscious, at least a little.

The experiment of the Cogita Consortium was not up to his statements, they supported the critics, because he did not test the fundamental aspects of theory. “As researchers, we have a duty to protect the public from scientific disinformation,” wrote dr. Lau and his colleagues.

Their letter, published online in September 2023, led to a storm of debate on social media. The authors wrote a comment to explain their objections in more detail; Last month he appeared in the magazine Nature Neuroscience.

Dr. Tononi and his colleagues responded to the diary with a reply. The Iit mortal letter “had a lot of fervor and little done”, they wrote, and the new comment “attempts to control the damage by adding a little Polish and a centered of philosophy of science”.

In the meantime, the card of the Cogita Consortium was still making its way through the review between peer. When he finally came out on Wednesday, he continued to draw divided opinions.

Anil Seth, a neuroscientist of the University of Sussex, was hit by the scope of the study and its discovery of deficiencies in each theory. “I'm happy to see him,” he said. “It's a great job.”

But the critics friction from Itt were based on their original opinion. Joel Snyder, psychologist of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, argued that the forecasts made by each team could also have been generated by other theories, so the experiment was not a precise test of either of them.

“It will generate confusion,” said dr. Snyder.

In one and -mail, Dr. Lau observed that the new study apparently did not reduce the long list of theories of consciousness. “From recent discussions, I don't have the impression that these challenges have done something to theories,” he wrote.

But Dr. Seth has still seen a value in mutual theories, even if it does not lead scientists to kill their ideas. “The best we can hope for a successful opponent's collaboration is that other people can change your mind,” he said.