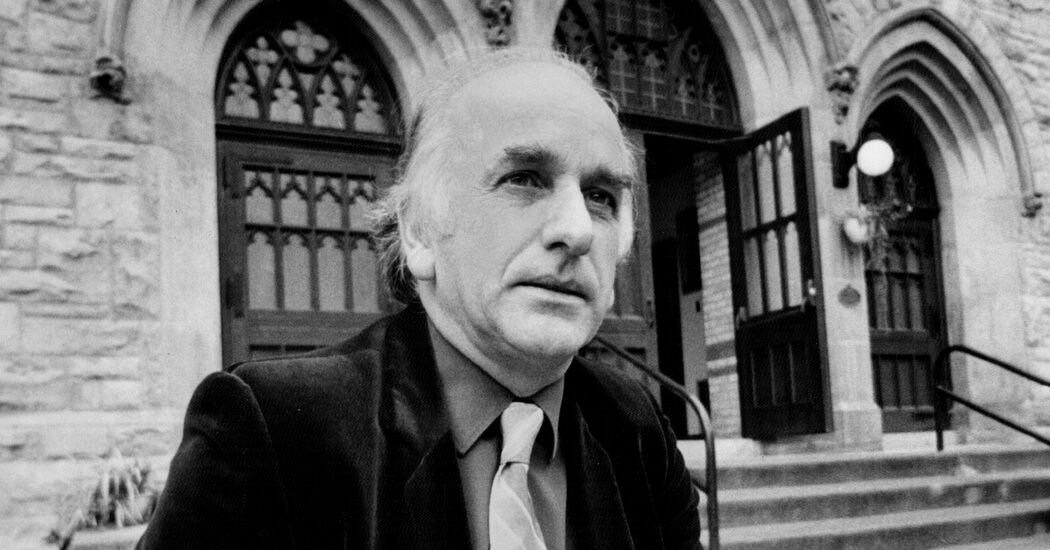

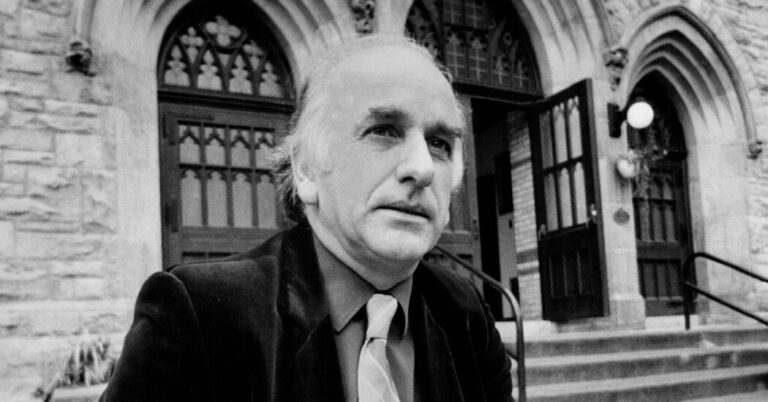

Derek Humphry, a British-born journalist whose experience helping his terminal wife to end her life led him to become a pioneer crusader in the right-to-diet movement and publish “Final Exit,” a best-selling guide to suicide, died Jan. 2 in Eugene, Ore. He was 94 years old.

His death, in a hospice facility, was announced by his family.

With a populist touch and a knack for speaking very firmly about death, Mr. Humphry nearly galvanized a national conversation about physician-assisted suicide in the early 1980s, a time when the idea had been little more than esoteric theory popularized by medical ethicists.

“He was the one who really put this cause on the map in America,” said Ian Dowbiggin, a professor at the University of Prince Edward Island and author of “A Concise History of Euthanasia: Life, Death, God and Medicine” ( 2005). “The people who support the notion of physician-assisted suicide absolutely owe him a big thank you.”

In 1975, Mr. Humphry was working as a journalist for London’s Sunday Times when Jean Humphry, his wife of 22 years, was in the final stages of terminal bone cancer. Hoping to avoid prolonged suffering, she asked him to help her die.

Mr Humphry procured a lethal dose of painkillers from a sympathetic doctor and mixed them with coffee in his favorite mug.

“I took the cup from her and told her that if she drank it she would die immediately,” Humphry told the Daily Record in Scotland. “Then I hugged her, kissed her and we said goodbye.”

Mr. Humphry chronicled the emotional, taboo and legally fractured pursuit of his wife’s hasty death in “Jean’s Way” (1979). The book, featured in newspapers around the world, was a sensation. Readers sent letters to the editor discussing the suffering of their loved ones. Many wrote directly to Mr. Humphry.

“I wish we had a solution like yours,” one woman wrote, describing the last eight weeks of her husband’s life as “a horror.” “The more beautiful, the more “love”. We did what others forced us to do and experienced that terrible “death” that the medical world gives by prolonging life in every possible way.”

In their letters, some readers asked for instructions to help their dying loved ones. That prompted Mr. Humphry, since remarried and working in California for the Los Angeles Times, to think about creating an organization to advocate for assisted suicide and end-of-life rights for terminally ill people.

Ann Wickett Humphry, his second wife, suggested using Hemlock as a title, “arguing that most Americans associate the word with the death of Socrates, a man who debated and planned his death,” she later wrote Mr. Humphry in an updated edition of “Jean’s Way.”

In August 1980, they rented the Los Angeles Press Club to announce the establishment of the Hemlock Society, which they ran out of the garage of their Santa Monica home.

The organization grew rapidly. In 1981, he issued “Let Me Die Before I Wake,” a guide to medications and dosages to induce “peaceful self-surrender.” The group also lobbied state legislatures to enact laws making assisted suicide legal. In 1990, the Hemlock Society moved to Eugene. At that point, it had more than 30,000 members, but the right-to-diet conversation hadn’t yet reached most dinner tables in America.

That changed spectacularly in 1991, after Mr. Humphry published “Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Surrender and Assisted Suicide for Death.” The book was a 192-page step-by-step guide that, in addition to explaining suicide methods, provided manna-like tips for exiting gracefully.

“If you are sadly forced to end your life in a hospital or motel,” he wrote, “it is polite to leave a noted apology for the shock and inconvenience with the staff. I have also heard of an individual who left a generous tip to a motel staff.”

The book quickly went to No. 1 in the hardcover recommendation category of the New York Times Best Sellers list.

“This is an indication of how large the issue of euthanasia looms in our society now,” said bioethicist Dr. Arthur Caplan in 1991. “It’s frightening and disturbing, and that kind of sales figure is a blow across the board. ‘arc. It is the strongest statement of protest of how medicine is dealing with terminal illness and death.”

Reactions to the “final exit” were generally divided along ideological lines. Conservatives blew it.

“What can be said about this new “book”? In One Word: Evil,” University of Chicago bioethicist Leon R. Kass wrote in the commentary magazine, calling Mr. Humphry “The Lord High Executioner.” “I didn’t want to read it, I don’t want you to read it. It should never have been written and doesn’t deserve to be dignified with a review, let alone an article. “

But progressives embraced the book, even as public health experts expressed concern that the methods it established could be used by depressed people who were not terminally ill.

“I read ‘Final Exit’ out of curiosity, but I’ll keep it for another reason — because I can imagine, having once nursed a cancer patient, the day I might want to use it,” New York Times columnist Anna Quindlen wrote, adding, “And if that day comes, whose is it, really, but mine and that of those I love?”

Rather than worry about the book’s contents, Ms. Quindlen said, “We should be looking for ways to ensure that a dignified death is available in places other than the mall chain bookstore.”

Derek John Humphry was born on April 29, 1930 in Bath, England. His father, Royston Martin Humphry, was a travel salesman. His mother, Bettine (Duggan) Humphry, had been a fashion model before she married.

After leaving school at the age of 15, Derek got a job as a newspaper messenger. The following year, Bristol’s Evening World hired him as a reporter. He went on to report for the Manchester Evening News and the Daily Mail before moving to London’s Sunday Times and then the Los Angeles Times.

Before turning to books about death, Mr. Humphry wrote “Why They’re Black” (1971), an examination of racial discrimination written with Gus John, a black social worker; and “Police Power and Blacks” (1972), about racism and corruption in Scotland’s backyard.

Mr Humphry was also a polarizing figure within the right-wing movement.

In 1990, he and Mrs. Wickett Humphry divorced and fought bitterly in the media. She called him a “fraud”, accusing him of leaving her because she was diagnosed with cancer. Mr Humphry denied the allegation.

“This has been a very shaky marriage,” she told the New York Times in 1990. “This is extremely painful, as bad as Jean’s death. I lost my home; I lived in a motel for three months.”

Mrs. Wickett Humphry killed herself in October 1991.

In a video recorded the day before, he expressed doubts about the work they had done together, including helping his parents end their lives at home.

“I walked away from that house thinking we’re both murderers,” he said in the video, which was reviewed by the Times.

Mr. Humphry went into “damage control” mode, he told the Times. He placed a half-page advertisement in the newspaper explaining his side of the story.

“Unfortunately, for much of her life, Ann was dogged by emotional problems,” the ad said, adding that “suicide for reasons of depression was never part of the Hemlock creed.”

Mrs. Wickett Humphry’s death and reservations about the right-to-diet movement caused strain within the Hemlock Society. Humphry resigned as executive director in 1992 and started the Euthanasia Research and Guidance Organization.

The Hemlock Society eventually sprouted into several new groups, including the Final Exit Network, which Mr. Humphry helped start.

He married Gretchen Crocker in 1991. She survives, along with three children from her first marriage; three grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.

Lowrey Brown, a Final Exit Network “Exit Guide” who helps plan spa patients, said in an interview that his clients sometimes credit Mr. Humphry and “Final Exit” for giving them the courage to ask end to their lives.

“It was the Hemlock Society and the book ‘Exit Final Exit’ that really crossed the threshold into bringing it into the living rooms of ordinary Americans as a topic of discussion,” Ms. Brown said. “You could talk about it at the Thanksgiving dinner table.”

If you have thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Laneline or go to Parlaofsuicical.com/resources For a list of additional resources.