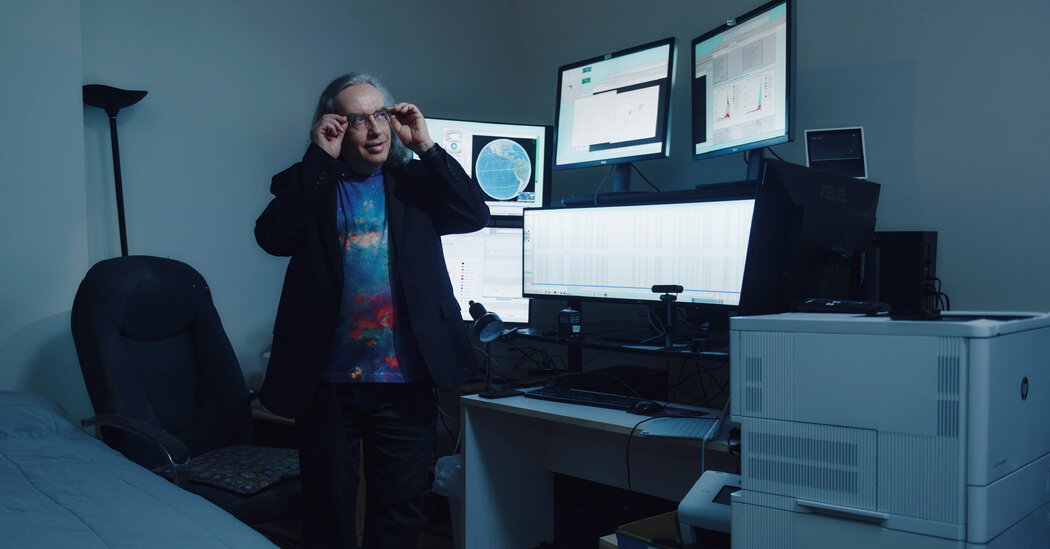

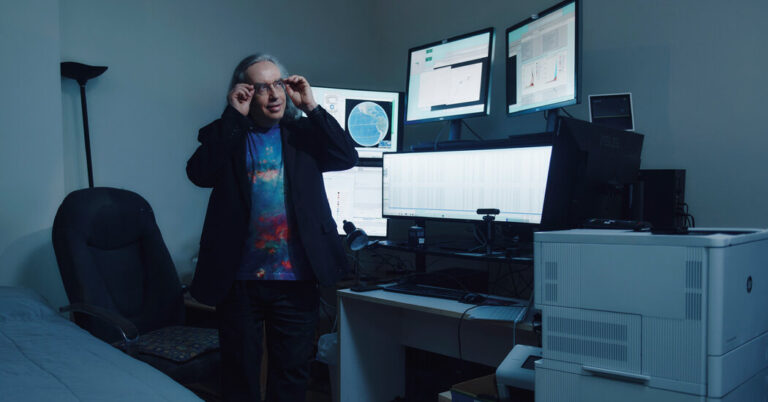

Jonathan McDowell is a reference expert for everything Spaceflight. Thousands of subscribers have read his report on the monthly space and many more people have seen it on cable news and other multimedia platforms that explain unexpected events in orbit.

But this has always been his secondary concert: for 37 years, Dr. McDowell was a specialist in X-ray astronomy at the Harvard-Smithsonian Astrophysics Center. At the beginning of this year he announced that he retired from the role and also leaving the United States for Great Britain.

The decision was partly pushed, he said, from the ongoing pressures on the budget of federal science, made more complicated by political changes by the inauguration of President Trump.

“It simply does not seem that the opportunities will be there to be an effective scientist and an effective person who builds the scientific community in the United States,” said Dr. McDowell. “I don’t feel proud to be an American as it once was.”

Born with double citizenship in the United States and Great Britain, Dr. McDowell joined Harvard-Smithsonian Astrophysics Center in 1988 and leads the group of scientific data systems for the Nasa Chandra Rays Observatory, a space telescope in its 26th year.

In the next phase of his career, said dr. McDowell wants to devote more time to document what is happening in space.

With an accent that joked is becoming decidedly more British while preparing to move abroad, Dr. McDowell spoke with the New York Times of what he guides his passion for space. This conversation has been modified for brevity and clarity.

What did your interest in space arouse?

There were really two paths. The satellites and the space really came from the Apollo program. I remember having returned home from school to northern England. I saw the moon in the sky and I thought: “Next week, for the first time, humans will be up there. They will be in another world”. This made me crazy like a 9 -year -old boy.

The astronomer side came from asking where we come from, what was the true story of how the universe became. This pushed me towards interest in cosmology at an early age. My father was a physique, and all my babysitters were also. In a sense, I did not realize that there was another option.

Another great influence was “Doctor Who”, which I started looking at the age of 3. This has imbued me with a sense of wonder on the universe and the idea that a crazy person can help the way humanity interacts with it.

All these things have joined to make me fascinated by what is out there.

In the British school system, we specialize in advance. I was making orbital calculations since the age of 14 and I learned the Russian so that they could read what the astronauts of Soyuz were doing. I continued to do a doctorate of research. At the University of Cambridge, so I got to go out with people like Stephen Hawking and Martin Rees, the current real astronomer. It could not have been a better training.

On the side, I was taking advantage of my technical skills to deepen the space flight. At the time, the media did not really cover the space, so this forced me to do my research.

Is this what led to the creation of the report on Jonathan’s space in 1989?

I had just moved to the Astrophysical Observatory of Smithsonian, which was once a space for space information for the public in the 1950s. Public affairs started bombing me with questions that they were still receiving from the public, therefore for self -defense, I started preparing a briefing for them on what was happening in space every week.

Someone recommended to put the briefing on Usenet, a sort of precursor on the web, which did not yet exist. With my surprise, it was popular. And I never looked back.

I took a more international vision of most of the news sources, particularly in the United States. I gave the same weight to what the Russians, the Chinese and the Europeans were doing. This helped me earn a reputation and people in the space sector started sending me mouths of information.

Why did you keep the space free relationship?

Honestly, most of the work I am doing for myself anyway. I am the reader n. 1. But now I also have this role of being someone who trusts what is really happening. I can keep that reputation for independence and objectivity if I do not take direct money for this.

How have Space Flight and Space Exploration changed during your life?

I grew up in the 1960s during the era of superpower. They were the United States, the Soviet Union and the Cold War. In the 70s, space became more international. China, Japan, France and others have started to launch their rockets and satellites. So in the 90s, we saw a turning point for marketing, both in communications and in animaging. And then in the 2000s and 2010, there was another change that I call democratization, in which low cost satellites made space in the budget of a university department, a developing country or a start-up.

The most important thing of the space in 2025 is not that there are more satellites, but that there are many more players. This has implications for governance and regulation.

Another way of thinking about how things have changed is where the border is located. When I was a child, it was orbit the low earth. Now, the border is out close to the asteroid belt and the moon and Mars are becoming part of where humanity comes out, perhaps not yet as people, but with robots. In the meantime, the orbit of the lower land is so normalized that it does not take a space agency to face it. Call only spacex.

How are you going to spend the pension?

The United Kingdom has recently been active to push for what we call space sustainability. They are committed to using space, but responsibly. I hope I can be involved in those efforts.

Fill out a large catalog of spatial garbage around the sun that the American spatial force does not keep track. At this moment it is not one’s work to keep track of it. We really have to put our act together for the most distant things, what we are sending between the planets, because it returns years later. We think it is an asteroid that will hit the earth, when it is really just a stage.

Most of the historians of the space focuses on people, not on hardware, so another aspect of all my ShTTK is documenting what the spatial projects have actually done. I have immersed the libraries of the spatial agencies for 50 years. I have about 200 bookstores of a library currently in 1,142 boxes. Half of things are probably scattered on the internet. But a significant subset is quite rare.

Obviously everything must be scanned and it will take me years. I have to find a new home for the library, somewhere that is a reasonable journey from London. My plan is that when it is disimalized, I will make it available by appointment to anyone who wants to come to do research.

What are you motivating to record human activity in space in such a meticulous way?

As an astronomer, I think of scales for a long time. I imagine people in a thousand years, perhaps at a time when more people live outside the earth than on it, who want to know this critical moment of history when, for the first time, we were entering space.

I want to preserve this information so that it can reconstruct what we have done. Here I am writing. Not the audience today, but to the public in a thousand years.