This article is part of NeglectedA series of necrologists on extraordinary people whose deaths, starting from 1851, have not been reported on time.

Joyce Brown's New York minute lasted longer than most. Secretary of the past, Brown became homeless in 1986 and began to camp on a heating grid on the second Avenue and the 65th Street in Manhattan.

About a year before being taken from the city's officials, involuntarily engaged in a psychiatric hospital – where it was declared a mind of mind – and with data force. Brown, who was better known as Billie Boggs, was the first homeless man to become at the center of the recently expanded initiative of the mayor I. Koch to face the growing visibility of the homeless and the not treated mental illness.

But, as he would have said later in the interviews, the city chose “the wrong one”. Unlike the dozen of other people who would have to face similar destinies, he said he knew his rights and would have started exercising them the following day.

What followed was a main cause focused on mental health, civil freedoms and the involuntary psychiatric treatment of the homeless. “I'm not crazy,” Brown would say. “Only homeless.”

In a short time, Brown was loft from the sidewalk to the limelight, with a vortex of interviews on talk and news programs.

When Brown died of a heart attack on November 29, 2005, at 58 years old, he had been forgotten for a long time.

But the repercussions of his transitory fame still echo on the sidewalks and metropolitans of the city, while the governor Kathy Hochul and the mayor Eric Adams have introduced their initiatives to face the homeless in New York, including involuntarily in the hospital people in psychiatric crisis.

Joyce Patricia Brown was born on September 7, 1947 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, the youngest of six children, most of whom was born in the South Carolina and Florida.

His father, William Brown, told the enumerators of the census in 1950 that he is unemployed. Her mother, Mae Blossom Brown, worked in a factory assembly baggage.

Some time after graduating from high school, Joyce Brown worked as a secretary for the Elizabeth Human Rights Commission, where he may have learned one thing or two on his constitutional privileges. At the time he also worked as an employee for the mayor of Elizabeth, Thomas G. Dunn, and for Thomas & Betts, a manufacturer of electrical equipment, according to a death warning from Nesbitt Funeral Home by Elizabeth.

At 18, however, he was dependent on cocaine and heroin and was stealing money from his mother. His mother died in 1979, who, said his relatives, could have emotionally triggered a further descending spiral.

In 1985, he had lost his job. In turn he lived with his sisters in New Jersey and was briefly treated in clinics and hospitals. The efforts of her sisters to help her cause topics and in 1986 he moved to Manhattan, where he made his house on the sidewalk near a Swensen ice cream shop in the East Side Upper, urinating and defecating outdoors nearby.

He adopted the name Billie Boggs, a twisted tribute to Bill Boggs, a television conductor of Wnew (now Wnyw), with whom he had expressed himself.

For some regular neighbors and passers -by, it has become a New York device, the type you don't find in the guides; They would conversion to her for the news. For the others, it was a threat: cure and shout racial epithets, in particular to black men, and even to give people a handful.

Her sisters tried to have hospitalized her. But the doctors said he did not present a danger for herself and released it.

On October 12, 1987, after being monitored for months based on a Koch administration strategy known as the help of the project (the initials represented the homeless emergency connection project)-and the homeless homelessness, where it was admitted and injected with a medical drug with medical agriculture and medicine and psychiatric care.

The next day, according to an article from 1988 in the New York magazine, he called the New York Civil Liberties Union from a public phone to the hospital. Norman Siegel, executive director of the organization, was one of the lawyers assigned to his case. In court, a psychiatrist from Bellevue presented a diagnosis of “chronic paranoid schizophrenia”.

That night, one of his sisters recognized him from a sketch in the classroom on television news.

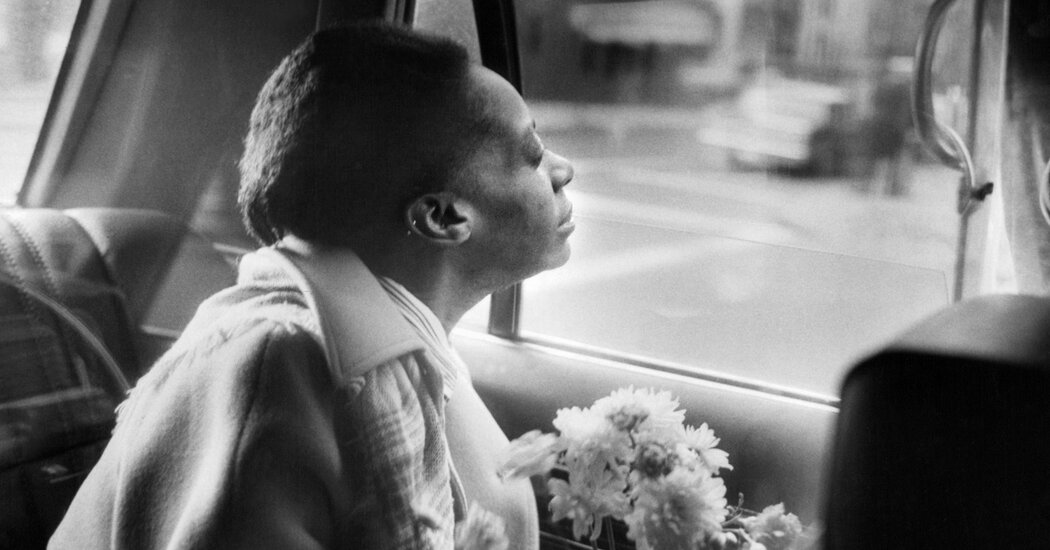

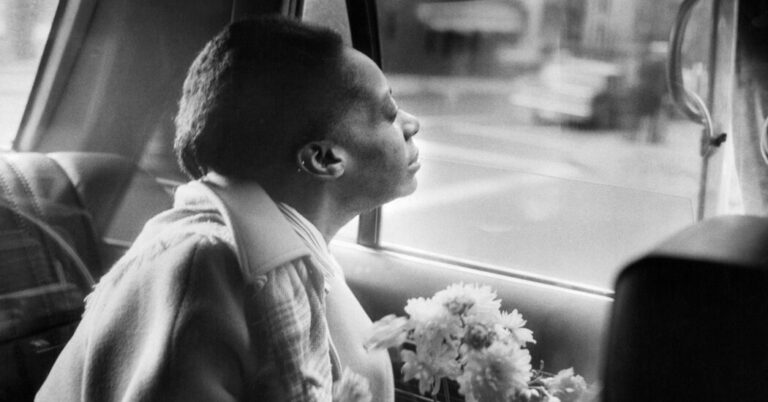

That image was clearly contrast to a photograph produced by his family, who showed a smiling brown, wearing a red dress and golden earrings while he was embraced by a man in tuxedo with a pink bow tie, his sisters who smiled in the nearby camera.

“This was my sister,” said one of the sisters. “This was us.”

A judge of the Supreme Court of the State established that Brown “was unable to take care of his essential needs” and ordered that he was released, but remained in Bellevue while the city appealed to the decision. The city won the appeal, but after a subsequent appeal by Brown's lawyers, a judge established that he could not be treated by force. That appeal was dropped when Belvue released Brown, saying that it makes no sense that he could not receive the hospital treatments. He had spent a total of 84 days there.

Soon he evolved into a media star, a symbol of justice that, his lawyers said, presented himself in his lucid and articulated interviews as a more or less rational example of urban bivacking he was, he said, “under surveillance” for months “as if I were a criminal”.

“In a civil society you don't go around collecting people against their will and bringing them to the hospital when they are healthy only because of a mayor program,” he told Morley Sacher for a 1988 segment of the CBS news program “60 minutes”. “All this is political. I am a political prisoner because of the mayor Koch.”

In the same segment, the mayor Koch insisted on the fact that the defecation on the street was “bizarre” and said that Brown's ability to speak articulated on the camera showed the effectiveness of his hospitalization and the drug that had been given to her.

That year Brown also appeared in “The Phil Donahue Show”, after being equipped by Bloomingdale and kept a lesson on a Harvard Law School forum in which he offered a “road view” of the homeless. The offers of books and films flooded the offices of the New York Civil Liberties Union. The Associated Press called it “the most famous homeless in America”. At his Moscow summit with Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the Soviet leader, in 1988, President Ronald Reagan invoked his case as an example of freedom in contrast with Moscow policy to retain political dissidents claiming to be ill.

“Rather than talking about me, why don't the president help me get permanent accommodation?” Brown was mentioned as mentioned.

In the wake of Brown's case, the project had to face public control and criticisms. The momentum of the program blocked and in the end it was suspended. The cause of Brown continues to act as a previous one in the debates on mental health, the homeless and the civil freedoms.

After Brown was released, he worked briefly as secretary for the Civil Liberties Union. But he left why, he said, he didn't like work.

“The boiling I had always admired dissipated,” Siegel said about her in an interview.

He gained; His pace slowed down; It may have been medicated again for a while. Around 1991, he moved to a supervised group house for previously homeless women, but he also returned to the street in Panhandle, saying that his sisters had delayed to her more than $ 8,000 in social security checks. He continued to live with $ 500 per month in payment for disability and avoided printing.

When Brown was initially released by Bellevue, he was against the recommendation of two judges of the Supreme Court of the dissenting state. “We could get closer to time,” they wrote, “when the problem of homeless people will face sincere and realistic attitudes and resources”.

“Now,” said Siegel, “35 years later, the hopes of the dissenting judges are unfortunately not yet materialized.”